It can be said with some certainty that Code Red, produced by Project Prometheus, is a work that will leave an impression upon today’s viewers. Some works, as a result of their thematic content and formal features, become artistic documents of contemporary times. Though not perfect, Code Red is to my mind a significant production, because it emerges out of the womb of the present times and becomes an unerring index of such times.

নয়ে নাটুয়ার হালের উপস্থাপনা মৈমনসিংহ গীতিকা : https://t.co/tZp1fY8hpU#bengalitheatre | #kaahontheatrereview pic.twitter.com/exaASYVJlq

— kaahon (@kaahonwall) May 25, 2017

These days original plays in Bengali are rare – most productions are reworkings of plays and other texts, domestic and foreign. In this sense, Code Red is part of this trend, as Indudipa Sinha (also director and choreographer) has written the play based on two texts – Matei Visniec’s French play The Body of a Woman as a Battlefield in the Bosnian War (1997) and Rabindranath Tagore’s poem, The Child (1931, translated by the poet as Sishutirtha). Though not original, Code Red can claim a degree of originality because the creation of a new text by seamlessly fusing two texts separated by language, time of publication and context is made possible only through an act of reading that is creatively original. Anxious at the rise of Indian nationalism modeled upon the European brand of nationalistic fervour and at the West’s worldwide export of its ideology of a mechanical, material civilization, Tagore wrote The Child, towards the close of which poem the birth of a newborn heralds hope for the whole of mankind. On the other hand, Visniec penned his play against the backdrop of the devastating ethnic conflict in the former Yugoslavia, the title of which suffices to indicate that he is particularly concerned with the way in war takes on a gendered nature so that bodies of women become battlefields for rampaging masculinity to ravage. There is, at the close this dark play too, a possibility of a birth. Indudipa Sinha has blended these two texts, which do have not much in common between them other than the motif of a birth at the end, with such felicity that it seems the two texts were indeed waiting to cross borders of culture, time and nations to fuse into each other.

As part of her blending strategy Sinha has taken a few bold decisions that have enriched Code Red. 1) Just as she has not attempted to fix the identities of the ‘Wise man of the East’ (Gautam Buddha? Rabindranath himself?), the Man of Faith (Mahatma Gandhi?) and the newborn (Jesus Christ? The Man Supreme?) of The Child, she has not allowed the weight of Freud’s theories as present in The Body to unduly burden Code Red. Code Red has not lost touch with philosophy or theory, but not at the expense of its requirements as drama. Rather Sinha has emphasized, in order to serve the cause of drama, the elements of journey and quest (fundamentally psychological in one, literal in the other) present in both texts. 2) Sinha changes the name of the traumatized rape victim Dorra of the French play to Mati (earth) in Code Red, which allows Mati to be instantly identified with the earth-mother of Rabindranath’s imagination. Also, with Dorra becoming Mati, this ecofeminist idea takes root that the earth does not exhaust its fecundity despite the limitless exploitation inflicted upon it by patriarchal and greed. More importantly, this change of name allows for performing the idea (without which there can hardly be any theatre) that life triumphs over death as a result of the eternal fertility of the earth.

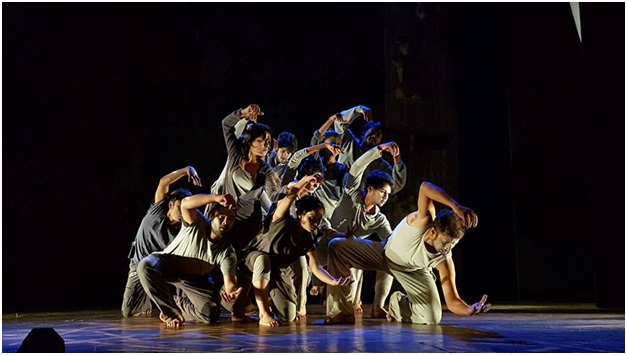

As director, Indudipa Sinha privileges performance and thus she blends here too; she blends dance with acting. As choreographer, she is eclectic – she constructs the dance in Code Red primarily on what is known as contemporary form of dance (which comes inclusive of many forms of dance), but infuses it with elements from Kathhak, Kathakali and other dance forms having originated from the martial arts. The knowing viewer will be alert to this that in certain formations Sinha as choreographer has alluded to such dance texts as the Tanushree Shankar-directed Sishutirtha or that portion of Dimitris Papaioannou’s Nowhere which is a tribute to Pina Bausch.

To come to the staged production, it must be pointed out that the slideshow presented at the beginning of the performance and immediately after the interval only goes to prove that the makers of the play failed to capitalize on the opportunity of making Code Red a full-blown multimedia audio-visual performance text. The background musical score designed by Dishari Chakraborty came across as infected with the malady of excessiveness – he might wish to consider the possibility of using snatches of silence as part of the score. Dinesh Poddar had to deal with the difficult problem of designing lights for a play invested in exploring the dark sides of life (war, rape, psychological trauma) – how does one make darkness visible through the use of light? It goes to his credit that Poddar has expertly handled his challenge. The light design at the very end of the play reminds one of Poddar’s own design for another popular production. Krishnendu Adhikari (as Joy) ably performs, through subtle adjustments in dialogue delivery and body language, the journey of his character from being a self-assured psychologist to becoming a war-ravaged broken man. In some sequences where Krishnendu and Gulshanara Khatun (Mati) perform in tandem, the differences in the scales at which they speak create a variance that helps distinctly etch out the two characters. I had a feeling that the many entries and exits disturbed Gulshanara’s concentration – in some scenes she took a fair bit of time before she could inhabit her character. Those who danced put their hearts into their dancing and it is a shame they cannot all be mentioned by name for constraint of space. Those who dance fluently would do well to bear in mind that during group performances it does not add to visual pleasure when one or two are seen dancing ‘better’ than others. The extent to which Code Red is dance-dependent is proven by the fact that most of the best dramatic moments are created through dance – the springing out of life from the depths of a mass-grave or the wail of the embryo in the womb are scenes that the audience will hopefully bear in their minds for a long time.

I will conclude by mentioning two points. 1) The original French play has two women as protagonists – in Code Red one of them becomes a man (Joy). I will primarily read this change as a (gendered) political decision where the playwright and director Indudipa Sinha has commendably separated patriarchy from male hood. Secondly, that Sinha does not take the opportunity that had presented itself to keep both the female characters and reserve one for herself to enact augurs well for the practice of theatre, which is after all not a space for an individual to parade all her various skills. 2) Apologizing for being overtly subjective at this point of the review, I will go on to confess that Code Red managed to take to me various texts at different points of time – for example, Mati opening her legs in response to something said by the psychologist took me to Sadat Hasan Manto’s stories, while the promise of new life despite all odds took me to Moushumi Bhowmik’s song Chithhi (The Letter). Please watch Code Red, if only to see which text you are taken to by it.

Dipankar Sen