The recently concluded Kolkata International Film Festival turned out to be the most obvious next step in the new direction adapted by the Festival authorities since last year. There have been more of renovations and facelifts, a Bollywood star-studded inauguration, presence of Tollywood celebrities and money spent on competitions. As a collateral, selection, scheduling and sheer viewing experience seemed to have been less than satisfactory. Due to the unusually large number of films in competitive categories, Nandan I, which is undoubtedly the finest venue, had to be almost entirely devoted for them. With Bengali premiere taking up most of the slots at Rabindra Sadan; Documentaries and Short films occupying Sisir Mancha, large number of films from the ‘Cinema International’ category, which screens the selected films from contemporary world cinema had to be pushed to the extreme fringes at venues such as Nazrul Tirtha or Mani Square or City Centre-I, located far from the heart of the city. Then there is the set of usual nuisances such as interrupted projections, ill-behaved crowd with zero sense of etiquette and the relentless blast of the theme music that invades into the theatres during the quieter moments of the films.

Having said that, if one had concentrated solely on the Nandan area and nearby Navina, one’d have the opportunity to experience a fair share, if not comprehensive, of contemporary world cinema as well as older classics. The festival covered a considerable chunk of films from across the globe including the Golden Bear and the Palm d’Or winners, which is commendable to an extent, but there have also been glaring omissions such as the latest releases by Michael Haneke or Yorgos Lanthimos.

This section will cover Kaahon’s evaluation of KIFF ’17 in the form of short reviews of selected films, in three parts. The first part will be a selection of latest films by contemporary directors, the second part will look at films by directors who have been festival favourites at KIFF while the final part will be an overview of this year’s Retrospective of Thai filmmaker Pen-Ek Ratanaruang.

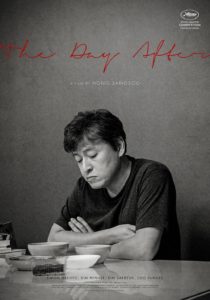

Prolific South Korean auteur Hong Sang-soo’s latest film has apparently triggered lukewarm responses from audience, followers and critics around the world. But nonetheless, it was certainly one of the best films to be screened in KIFF ‘17, barring the obvious old classics such as Satyajit Ray or David Lean, etc. Considering Hong’s body of work, the film has been strangely familiar and yet markedly different in terms of his approach and style, which is probably it wouldn’t gain him new followers and yet found detractors due to certain shifts in approach. The film is about a philanderer, recounted in a well-rounded narrative while treated with a minimal formal style.

The plot begins with Ah-reum (Kim Min-hee of ‘The Handmaiden’ fame), a sensitive aspiring writer joining on her first day at work at a small-scale publishing house run by acclaimed critic, Bong-wan. However, she is not aware of the fact that she is a replacement for Chang-sook, who left the job a month ago, and has been Bong-wan’s mistress. Although Ah-reum’s first day starts uneventfully at the office, it soon takes a dramatic turn with the arrival of the Bong-wan’s wife, who’d found a love note addressed to her husband. She storms into the office and mistakes Ah-reum to be Chang-sook and violently attacks her. Although Bong-wan’s arrival pacifies the scenario to an extent, Ah-reum decides to leave the work. Things get further complicated when Chang-sook comes back and Bong-wan wants to rekindle both the personal and professional relationships.

acclaimed critic, Bong-wan. However, she is not aware of the fact that she is a replacement for Chang-sook, who left the job a month ago, and has been Bong-wan’s mistress. Although Ah-reum’s first day starts uneventfully at the office, it soon takes a dramatic turn with the arrival of the Bong-wan’s wife, who’d found a love note addressed to her husband. She storms into the office and mistakes Ah-reum to be Chang-sook and violently attacks her. Although Bong-wan’s arrival pacifies the scenario to an extent, Ah-reum decides to leave the work. Things get further complicated when Chang-sook comes back and Bong-wan wants to rekindle both the personal and professional relationships.

The most exciting thing about the film is the way it is structured as a closure-driven narrative. There are long drawn conversations which are punctuated with events of a more dramatic nature. Thus, it becomes an insightful and at times even scathing study of Bong-wan’s character, thereby a reflection on masculinity in general, while a number of relationships disintegrate around him. And the narrative structure makes room for both observation, when the events are happening, as well as contemplation during the conversational moments. Hong exercises an almost Ozu-like restraint in these scenes and his precise use of humour makes his critique of masculinity even sharper.

Hong is certainly an undisputed master of the cinematic form and this film is not just marked by its emphasis on form, but it also keeps the film from turning into a typical dreary chamber drama about human relationships. The film comprises of precise and pre-meditated long takes and minimal movements of the camera, thereby rendering a fixed viewer’s position. While this non-intrusive approach helps with the realism, Hong applies stark zoom in and zoom outs at particular points in the narrative which create intended breaks within the narrative experience, keeping it from becoming immersive and ensuring a distance from both characters and events. Shot in black and white, the greyscale becomes an evocative context for a suitably adult narrative.

Winner of the Jury Prize at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, Loveless by director Andrey Zvyagintsev has definitely been one of the biggest attractions at the KIFF this year. It has also turned out to be the biggest disappointment. After bursting on to the scene with his debut feature The Return in 2003, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, Andrey Zvyagintsev’s curve has been more or less steadily declining into unseen depths of mediocrity.

With its cold and bleak treatment, the film certainly remains true to its name and that’s more or less about it. The film is centred around the disappearance of Alyosha, son of Zhenya and Boris, a couple in the midst of a bitter divorce. Boris is involved with a younger woman who is already pregnant with his child, and Zhenya has a new wealthy lover. Apparently when both parents are out of the house having sex with their respective partners, the child goes missing. A long and exhausting search ensues which reveals the father to be an indecisive loser and the mother to be cold hearted monster.

The single point problem with the film is that it is an absolutely pointless and a pretentious aesthetic exercise. It deals with a number of issues and concepts in the course of the narrative including couple, marriage, family, but everything is just ‘jaw dropping’ superficial. There is no critical engagement with anything and everything remains unproblematized. All it succeeds is taking an extremely moralist and regressive stance on divorce and taking the parents on a guilt trip. The film locates within the missing child trope, the misery as an outcome of divorce. In fact, the entire divorce angle actually adds nothing to the narrative since both the parents are portrayed as self-centred and irresponsible. So, the film literally gets divided into convenient binaries; negligence about their child and thereby suffering from guilt. Frankly, with a far less command on film aesthetics, Shibu-Nandita are doing the same thing with films like Praktan and Posto.

Loveless is symptomatic of the dominant practices in European Art House Cinema, where the merit of the film is merely reduced to attractiveness of the image and usage of visual idioms and metaphors. This film is filled with overly aestheticized frames and compositions and cliched metaphors. The ice-covered landscape with barren trees, the woman asking for an apple after having sex, a window serving as a frame-within-a-frame or a piece of tape swaying in the wind stuck on a branch as the spirit of the child, everything is not just dated and hackneyed, but their articulation is simply imposed within a narrative which is utterly clueless from the beginning. Besides two compelling performances by Maryana Spivak as Zhenya and the actress playing her domineering mother (strangely not mentioned in wiki, imdb, etc.), the film fails to bring anything to the screen worth engaging with.

Hard hitting and brutal, Sergei Loznitsa’s A Gentle Creature is a harsh critique of the Russian bureaucracy. A monolith system still bearing the Stalinist legacy in post-communist Russia, the film unfolds against a complex mesh of secrecy, paranoia and apathy. The film’s intent can truly be described as casting an unflinching gaze into the abyss and the unsettling viewing experience is indeed that of the abyss staring back. Without a doubt, this has been the finest and certainly the most compelling film featured in this year’s Kolkata International Film Festival.

The titular protagonist of the film is a meek woman who lives by herself in some remote corner of the Russian countryside. When she comes to know that a package which she had sent to her husband, who is in prison, was rejected, the woman is determined to seek an answer. Thus begins a long and gruelling journey to another remote prison town in Siberia and all throughout her interactions with space and experiences with people keep growing more and more strange, absurd, cold and cruel. And as the nameless character moves across unnamed locales, the whole journey assumes an almost Odyssey like mythic overtone. Vasilina Makovtseva’s impassive and controlled performance as the protagonist provides an empty canvas which can perfectly capture the multiple shades of absurdity, nightmare and chaos unfolding around her.

Built on a rich texture of literary references, the film borrows the title and the spirit from the short story of the same name by Fyodor Dostoevsky. However, it seems more connected in narrative structure and experience, to Franz Kafka’s ‘The Castle’. In its harrowing and detail account of a rigid, unbending and authoritarian bureaucracy, the narrative acquires a spiral nature. Right from the smaller individual experiences, to the larger arc of the journey, things seem to be unfolding on an endless loop. This structural strategy becomes highly effective in terms of the film’s leap from its social realist paradigms into the realm of absurdity, especially the prolonged banquet in a dream which ends in a violent sexual assault, all perhaps within a dream…or not.

The film is shot in predominantly long takes and a largely warm toned colour palette by Oleg Mutu, who had trodden similar territories in the most iconic films of Romanian New wave such as The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (Cristi Puiu, 2005) and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu, 2007). His lens captures a hellish portrayal of a land by gazing at expansive landscapes, constricted interiors and mostly at faces with accentuated expressions, be it a grimace or a leer or a scowl. By placing the camera always in the middle of an action or a conversation and completely doing away with the shot-counter shot technique, there is always a sense of being surrounded by or imposed upon by a world which is utterly devoid of empathy.